More Valuable Than Gold

Spilling from alpine heights through the world’s first national park, the Yellowstone River — the longest free-flowing river in the lower 48 — winds north, past the century-old stone arch marking the border of Yellowstone National Park, and into a Montana valley called Paradise.

Wildlife abounds in this valley and the land surrounding it. Elk herds roam along the riverbed, raptors swoop over trout streams and antelope spring across the valley, sharing the space with human residents. Grizzlies, mountain lions and wolves complete the portrait of nature as it once was — predator and prey striking a balance.

Here, near the braided river and enfolded by rugged, 10,000-foot peaks, Darcie Warden preps for one of her favorite meditations — in a place that is now considered under threat.

The Paradise Valley and surrounding area face an uncertain future. Two gold mining proposals are slowly moving forward, and many say they would threaten water resources, wildlife and the quality of life that supports the region’s economy. One mine would perch on a prominent peak, while the other would literally sit on the border of Yellowstone Park. The proposals have spurred local businesses, residents and politicians on both sides of the aisle to declare that the Yellowstone ecosystem is more valuable than gold.

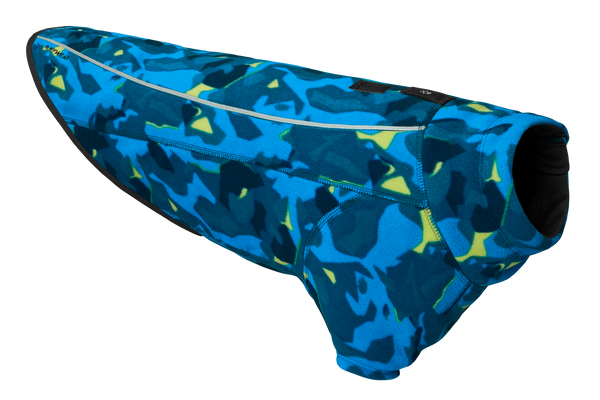

Darcie pulls two harnesses from her rig. Balto bounds back and forth, back and forth, always ready. Ever-skeptical Ruby cocks her head as Darcie clicks into skis.

Called skijoring, Darcie says it really feels like flying. To run, to pull, to move in perfect harmony is what these Alaskan husky siblings were born to do.

It's intense love for Balto and Ruby, three working together as one. It’s connection to this place that’s a home for her heart, drinking in the wind, the trees, and the beckoning mountains.

At a nearly century-old log cabin in the pines, they break for a drink and treats. It’s a welcome rest stop — Ruby’s energy is flagging. She’s averting her eyes and flopping into the fluffy snow at every pause.

With gold mining proposals poised to change the Paradise Valley, Darcie is part of the effort that is seeking solutions — ones that recognize that the area’s natural values are a tremendous asset.

Grassroots efforts are underway to prevent the sulfide gold mines that would pose a threat to these wild places and the livelihoods that depend upon them. Darcie is doing her part by working for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. For more than three decades, the nonprofit organization has focused on safeguarding the integrity of the Yellowstone ecosystem — 20 million acres of public lands across three states that includes Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks.

“I have this immense love for my dogs when I’m out with them on skis,” Darcie says. “It’s so meaningful for us, getting to jore in this very special place. It’s astounding — the Paradise Valley might not be part of Yellowstone National Park, but it has all the qualities of a national treasure.”

To secure the future of the area, Darcie says, would be to ensure future generations and their canine companions can also experience the magic she feels there with Ruby and Balto — their own memories in Paradise.